1. Introduction

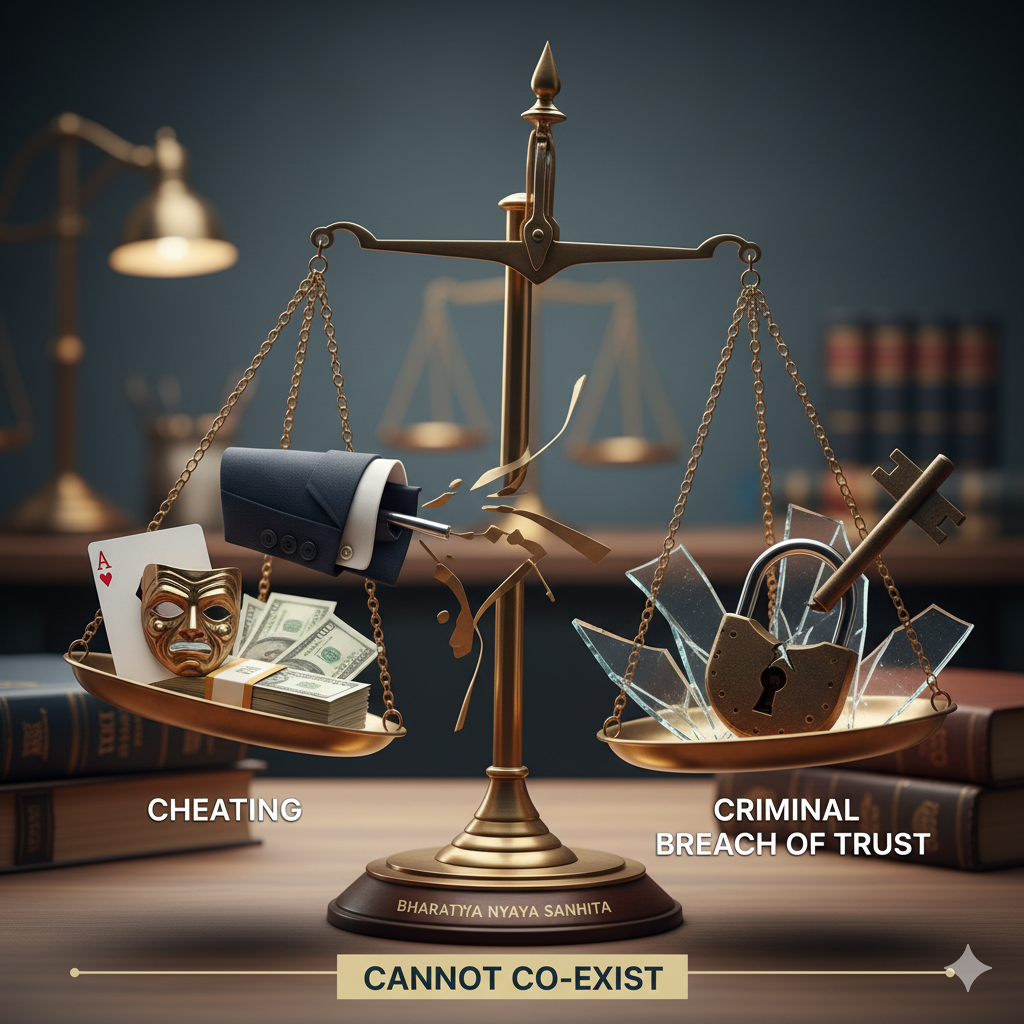

The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (BNS), replaced the colonial-era Indian Penal Code (IPC) with a modern criminal law framework rooted in Indian realities. Among its many provisions, two offenses continue to invite profound discussion: cheating and criminal breach of trust.

Both involve dishonest conduct, yet the law draws a clear and necessary distinction between them. Understanding this distinction is essential for law students, advocates, and anyone handling financial or fiduciary relationships.

Under the BNS, these offenses cannot coexist for the same act. The reason lies in the timing of intention, what lawyers call the mens rea. The moment when dishonesty begins defines the offense and decides whether a person should be charged under Section 318 (BNS) for cheating or Section 316 (BNS) for criminal breach of trust.

2. Evolution from IPC to BNS

The IPC of 1860 defined these offenses under Sections 415 (Cheating) and 405 (Criminal Breach of Trust). Over 160 years, courts clarified their scope and differences through consistent judicial reasoning.

The Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (2023) renumbers and rephrases these provisions as

- Section 316—Criminal Breach of Trust

- Section 318—Cheating

Although the numbering is new, the substance remains unchanged. Parliament preserved the distinction to avoid overlap, ensuring that one offense punishes deception at inception, while the other punishes betrayal of confidence after entrustment.

This continuity matters: precedents decided under the IPC continue to hold persuasive authority for BNS interpretation because the underlying elements of dishonesty, entrustment, and deception remain identical.

3. Cheating under Section 318 BNS

Statutory Basis

Section 318 BNS punishes any person who, “by deception, fraudulently or dishonestly induces another person to deliver any property or to do or omit anything he would not have done or omitted if he were not so deceived.”

Essential Ingredients

- The essential ingredient is the deception of a person through false representation or concealment.

- A dishonest or fraudulent inducement to deliver property or to take or omit an action is the essential ingredient.

- Dishonest intention at the time of inducement: the accused never intended to act honestly.

- The deceived person suffers the resulting harm or damage.

The essence of cheating lies in the initial intention. The offense is complete the moment the inducement succeeds, even if the property is not actually delivered later.

Illustration

If A persuades B to invest ₹2 lakh in a business that A knows does not exist, A is guilty of cheating. His dishonest intention existed from the very beginning.

Judicial Clarification

The Supreme Court in Hridaya Ranjan Prasad Verma v. State of Bihar (2000) 4 SCC 168, paras 134–136, held that “the intention to deceive must exist at the time of making the representation.”

If such intention arises only later, the case becomes one of breach of contract or breach of trust, not cheating.

Similarly, in Vesa Holdings (P) Ltd. v. State of Kerala (2015) 8 SCC 293, paras 8–9, the Court reaffirmed that every breach of contract is not cheating; criminal liability arises only when the dishonesty is present at inception.

4. A criminal breach of trust under Section 316 BNS

Statutory Basis

Section 316 BNS covers situations where a person, after being lawfully entrusted with property or having dominion over it, dishonestly misappropriates or converts it to his own use.

Essential Ingredients

- Entrustment of property or control to the accused.

- A fiduciary or trust relationship is established between the parties involved.

- Dishonest misappropriation or conversion for personal use.

- Dishonest intention arises after entrustment, not before.

Here, the initial possession is lawful, and the offense begins only when the person violates that trust.

Illustration

If a company cashier receives payments on behalf of the firm but later diverts the funds for personal expenses, the offense is criminal breach of trust, not cheating, because the possession was legitimate at first.

Judicial Clarification

In R.K. Dalmia v. Delhi Administration (AIR 1962 SC 1821, Headnote (iii)), the Supreme Court defined entrustment broadly, holding that it includes any dominion or control over property, not just formal trusteeship.

The Court explained that the dishonest intention in breach of trust develops after the entrustment, the precise opposite of cheating.

5. The Timing Test: The True Legal Divide

The timing of dishonest intention forms the cornerstone of distinction between these two offenses.

| Aspect | Cheating (§ 318 BNS) | Criminal Breach of Trust (§ 316 BNS) |

|---|---|---|

| When does dishonesty arise? | At the beginning of the transaction. | After property is lawfully entrusted. |

| How is possession obtained? | By deception or inducement. | By confidence or fiduciary relationship. |

| Nature of act | Inducing another to part with property. | Misusing property already entrusted. |

| Illustrative example | Taking money for a fake business. | Misusing funds received as an agent. |

Because the mens rea (mental element) occurs at different stages, it is impossible for both offenses to coexist in one transaction.

If deception existed from the start, there was no genuine entrustment. If entrustment existed, there was no deception at inception.

This logic was conclusively affirmed in Jaswantrai Manilal Akhaney v. State of Bombay (AIR 1956 SC 575, pp. 582–583), where the Supreme Court held that the two offenses are mutually exclusive.

6. Why the Distinction Matters

Understanding the distinction is not academic alone; it has practical consequences:

- Accurate Charge-Framing: Police and prosecutors must decide at the investigation stage whether the evidence shows deception or entrustmentnot both.

- Preventing Over-Criminalization: Treating civil disputes as criminal cases is legally improper; knowing this distinction prevents misuse of the criminal process.

- Judicial Efficiency: Courts can identify weak or overlapping charges early, saving judicial time.

- Educational Importance: Law students must know this distinction for exams, internships, and moot arguments, as it reflects a fundamental rule of mens rea analysis in criminal law.

7. Judicial Application under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS)

The BNS 2023 does not disturb the settled jurisprudence built under the IPC. Courts will continue to apply earlier precedents because Sections 316 and 318 BNS are conceptually identical to the old Sections 405 and 415 IPC.

This means that the “timing test” remains the controlling factor.

(a) When the case amounts to cheating

If the evidence proves that the accused never intended to perform his promise and used a false representation to secure property, it is cheating.

- Hridaya Ranjan Prasad Verma v. State of Bihar (2000) 4 SCC 168, paras 134–136: The Supreme Court held that “the intention to deceive must exist at the time of inducement.” A later failure to keep the promise does not convert the act into cheating.

- Vesa Holdings (P) Ltd. v. State of Kerala (2015) 8 SCC 293, paras 8–9: Reiterated that mere breach of contract is not cheating unless deception existed at inception.

(b) When the case amounts to criminal breach of trust

If property was lawfully entrusted and only later misappropriated, the offense falls under criminal breach of trust.

- R.K. Dalmia v. Delhi Administration, AIR 1962 SC 1821 (headnote iii): The Court expanded the concept of “entrustment” to cover any dominion or control over property. Dishonesty arises after entrustment when the property is misused.

- State of Kerala v. A. Pareed Pillai, AIR 1973 SC 326: Clarified that the accused’s initial possession was legitimate; criminality began only upon misappropriation.

(c) Why Both Cannot Coexist

The rule was made explicit in Jaswantrai Manilal Akhaney v. State of Bombay (AIR 1956 SC 575, pp. 582–583), where the Supreme Court stated that “Cheating and Criminal Breach of Trust are mutually exclusive; the existence of one necessarily negatives the other.”

The Court explained that if deception existed at the beginning, no entrustment could ever arise, and if entrustment existed, there could not have been deception at inception.

This doctrinal clarity is what the BNS continues to uphold.

8. Comparative Overview: Cheating vs. Criminal Breach of Trust

| Criteria | Cheating – § 318 BNS | Criminal Breach of Trust – § 316 BNS |

|---|---|---|

| Legal nature | Deception-based offence | Fiduciary-based offence |

| Initial control over property | Obtained by false representation | Obtained through lawful entrustment |

| Timing of dishonest intent | Exists at inception | Arises after entrustment |

| Victim’s role | Deceived to deliver property | Voluntarily entrusts property |

| Example | Taking advance for a fake project | Agent diverts client funds |

| Key Case Law | Hridaya Ranjan Verma, paras 134–136; Vesa Holdings, para 8 | R.K. Dalmia, headnote (iii) |

| Coexistence? | Cannot coexist with § 316 BNS | Cannot coexist with § 318 BNS |

9. Practical Implications for the Legal Field

(a) For Investigators and Prosecutors

When drafting an FIR or charge sheet, it is vital to choose the correct section.

- If the property was induced through falsehood, use § 318 BNS.

- If it was lawfully entrusted and later misused, apply § 316 BNS.

Mis-framing both charges together often leads to quashing under Section 482 CrPC for “abuse of process.”

(b) For Defense Lawyers

When the complaint confuses deception and entrustment, the defense can challenge the case by applying the timing test and citing Hridaya Ranjan Verma and Jaswantrai Akhaney.

A clear argument that the accused either (a) acted under a civil contract or (b) possessed lawful dominion can dismantle the charge of cheating.

(c) For Law Students

This distinction frequently appears in criminal-law papers, judicial-exam mains, and moot-court problems.

Students should memorize the timing rule and quote the exact paragraph references for credibility.

10. Illustrative Hypotheticals

- Fake Scholarship Scheme

A starts an online campaign claiming to offer scholarships but never intends to disburse them. → Cheating under § 318 BNS.

(Hridaya Ranjan Verma, paras. 134–136) - Partner Misusing Funds

B, a business partner, receives ₹10 lakh for a joint venture and later uses it to buy personal property. → Criminal Breach of Trust under § 316 BNS.

(R.K. Dalmia, headnote iii) - Supplier Delays but Eventually Delivers

C takes advance payment but faces supply chain delays. There is no initial deceit → Civil breach, not criminal.

(Vesa Holdings, para. 8)

11. Common Mistakes and Misconceptions

- Treating every commercial loss as cheating.

The law requires dishonest intention, not mere failure. - Framing both offenses in one charge.

Doing so violates the logical structure of criminal liability. - Ignoring fiduciary capacity in breach of trust cases.

Without proof of entrustment, conviction under § 316 BNS cannot stand. - Assuming intention can be inferred from non-performance alone.

Courts insist on initial intention, as seen in Vesa Holdings.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the difference between cheating and criminal breach of trust under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023?

The primary distinction under the BNS, 2023, pertains to the timing of dishonest intent.

In Cheating (Section 318), the accused has a fraudulent or dishonest intention from the very beginning and uses deception to make another person part with property.

In Criminal Breach of Trust (Section 316), the accused receives property lawfully, based on trust or a fiduciary relationship, and later misuses or converts it dishonestly.

Thus, one starts with deception, the other with confidence.

2. Can both offenses be charged together under the BNS?

No, both offenses cannot exist together for the same transaction.

The reason is doctrinal—one offense begins with dishonesty at inception (cheating), while the other begins with trust at inception (breach of trust).

The Supreme Court in Jaswantrai Manilal Akhaney v. State of Bombay (AIR 1956 SC 575) clearly held that these two offenses are mutually exclusive, since the mental state required for each is incompatible.

3. What are the relevant sections for these offenses in the BNS, 2023?

- Section 318—defines and punishes cheating (derived from Section 415 IPC).

- Section 316—defines and punishes criminal breach of trust (derived from Section 405 IPC).

Both sections carry the same core legal principles as the IPC but are written in simpler and updated language for modern interpretation.

4. What must be proved to convict a person for cheating under Section 318 of the BNS?

To establish cheating, the prosecution must prove:

- The prosecution must establish that the complainant was deceived.

- The prosecution must demonstrate that the complainant was induced to deliver property or to act or omit in a way that he would not have otherwise done.

- Dishonest intention at inception, i.e., the accused never intended to fulfill his promise.

This principle was clarified in Hridaya Ranjan Prasad Verma v. State of Bihar (2000) 4 SCC 168, paragraphs 134–136, where the Court held that intention at the time of inducement is the gist of cheating.

5. What are the key ingredients of criminal breach of trust under Section 316 of the BNS?

The offense of criminal breach of trust requires:

- Entrustment of property or control over it.

- There must be an existing trust or fiduciary duty, such as an employer-employee relationship, an agent-principal relationship, or a partnership relationship, among others.

- There should be no dishonest misappropriation or use of the property for one's own benefit.

- A dishonest intention may emerge later, following the entrustment.

This was explained in R.K. Dalmia v. Delhi Administration (AIR 1962 SC 1821), where the Court broadened the meaning of “entrustment” to include any lawful control or dominion over property.

6. How does the timing of dishonest intention determine which offense applies?

The moment the dishonest intention forms, it determines which provision applies:

- If it exists at the beginning, when the property is obtained, it is cheating.

- If it develops after lawful entrustment, when property is already held in confidence, it is criminal breach of trust.

This timing distinction was reaffirmed in Vesa Holdings (P) Ltd. v. State of Kerala (2015) 8 SCC 293, paragraphs 8–9, and Sushil Sethi v. State of Arunachal Pradesh (2020) 3 SCC 240, paragraphs 7.2–7.3.

7. Why is distinguishing these two offenses important in practice?

Distinguishing between these offenses ensures correct charge framing and a fair trial.

If police or prosecutors mix both for the same act, it weakens the case and may lead to quashing under Section 482 CrPC.

For law students and future advocates, understanding this distinction is vital for drafting, mooting, and interpreting the mens rea element accurately.

8. Is every breach of promise or failure to repay a loan considered cheating or criminal breach of trust?

No. A mere failure to perform a promise, repay a debt, or deliver goods does not amount to a criminal offense unless dishonest intention is proved.

For cheating, it must be shown that the accused never intended to perform from the start.

For criminal breach of trust, it must be shown that property was entrusted and then misused dishonestly.

If neither is proved, the matter remains civil, not criminal—a key principle repeatedly emphasized by the Supreme Court in Vesa Holdings (2015) and Sushil Sethi (2020).